History & Dual RightsThe Dual Rights Fund is used to support the Academy’s efforts to protect Attorney-CPAs with their right to practice as an Attorney, CPA, or both. This Fund is used for issues deemed critical to Attorney-CPAs. Click to Donate to the Dual Rights Fund

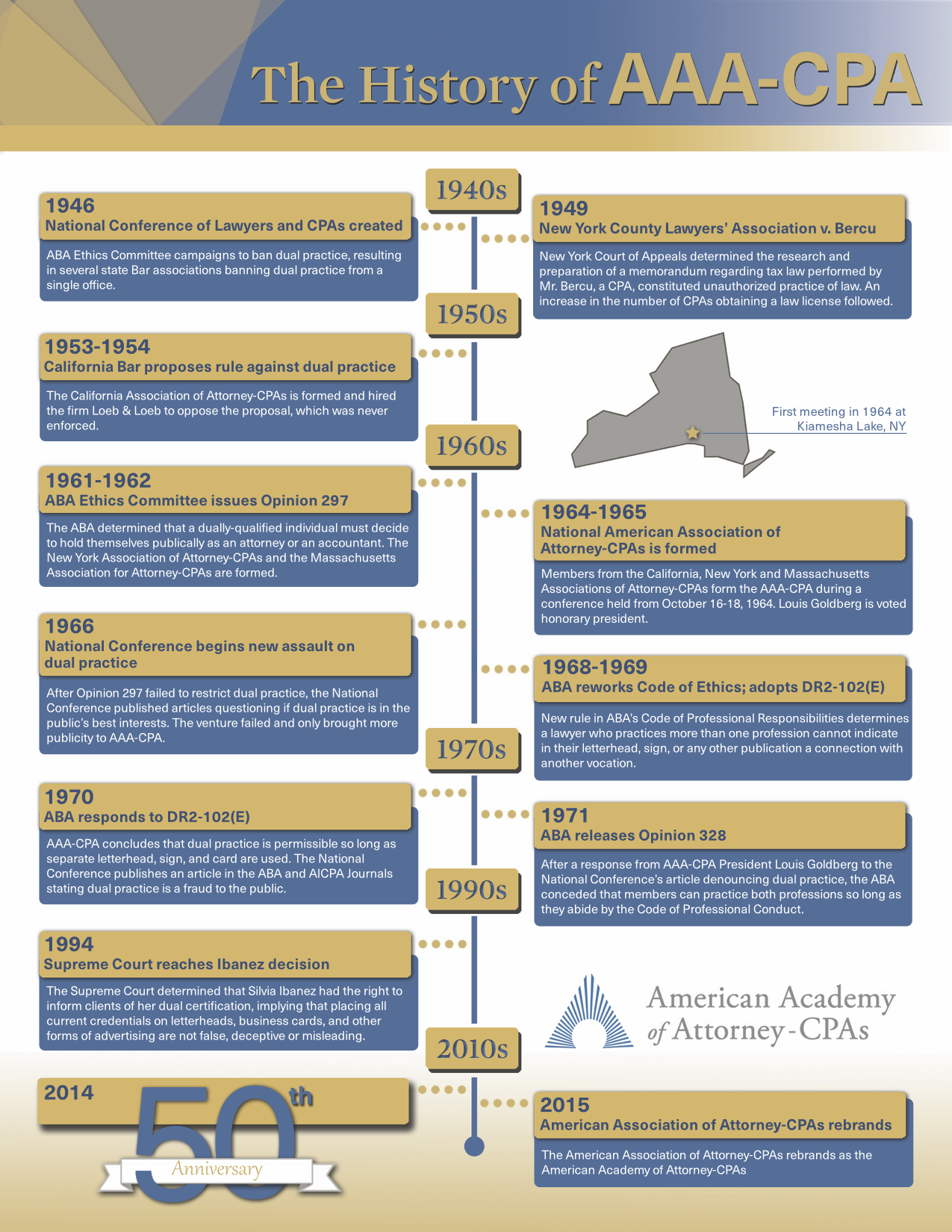

1946: Before AAA-CPA was formedABA and AICPA create the National Conference of Lawyers and CPAs (“National Conference”) made up of members from both organizations. The attorneys had a majority of one. The National Conference became the prime antagonist of dual practitioners for many years. On March 4, the National Conference promulgated questions touching dual practice to the ABA Ethics Committee and to the AICPA Ethics Committee. AICPA was not opposed to dual practice. The ABA Ethics Committee however, campaigned to outlaw dual practice. In October, the ABA Ethics Committee issues Opinion 272 which condemns dual practice from a single office but because of a lack out of unanimity in the Ethics Committee it did not foreclose the possibility of dual practice from separate offices. The ABA Opinions on dual practice were adopted by a few state bar associations and rejected by others; most of the states, however, remained neutral. IRS independently set its own rules in Circular 230 as to who (attorneys and CPAs) may represent tax payers before and prepare tax returns to be filed at the IRS. 1947-1950There arose conflict between attorneys and CPA regarding their respective roles (or turf) in tax practice. This culminated in the 1949 celebrated case of the New York County Lawyers’ Association v. Bercu, decided by the New York Court of Appeals. It held that the services rendered by Mr. Bercu, a Certified Public Accountant, constituted the unauthorized practice of law. Mr. Bercu advised a corporate client how to compromise an excise tax claim levied against it but he had done no work on the corporation’s tax return. He researched and prepared a memorandum on a question of tax law. Mr. Bercu performed similar work for other clients for $50 per hour as a tax consultant instead of $15 per hour as an auditor. Mr. Bercu was held in contempt, fined, restrained from the further practice of law, and was not able to collect his fee of $500. News of this decision influenced many CPAs to also obtain a law license and the number of dually licensed professionals began to increase. ABA and AICPA opposed each other as amici curiae in this case. Giving tax advice is in fact the practice of law. No one has ever contended to the contrary. The issue is whether it is the AUTHORIZED or the UNAUTHORIZED practice of law. Several interpretations of where to draw the line evolved as the income tax grew in amount and importance. Accountants (including CPA’s, Public Accountants, Enrolled Agents, and plain bookkeepers) began preparing tax returns because most lawyers felt their fees were too high for this type of work and they really didn’t want to do that. Calling themselves tax return preparers, consultants, accountants, and various other titles non-lawyers began preparing returns. Some interpretations were that the “mere” preparation of a return was an authorized practice of law by a non-lawyer but that doing any research required legal training and therefore was the unauthorized practice of law. Some interpretations were that it was okay for a non-lawyer to read a head note in CCH, but reading the underlying case was the practice of law. The National Conference of Attorneys and CPA’s (6 appointments by AICPA and 6 by ABA Tax Section and the Chair appointed by the President of ABA every third year) made a series of deals, the end result being that the preparation of tax returns was in fact the practice of law, but the authorized practice of law. 1951Harmony is restored between Attorneys and CPAs and the National Conference resumes activities. 1953California Bar or Court proposes a rule against dual practice. 1954California Association of Attorney-CPAs is formed. They engage the firm of Loeb and Loeb, who decline payment and work pro bono because they believe in the merits of our cause, prepare a brief opposing the rule. The Rule was not enforced. 1954-1964The California Association of Attorney-CPAs receives mail and requests to become a member from Attorney–CPAs in many different states. The California Association of Attorney-CPAs kept lists of names and addresses of each dual licensee from each state and advised those who contacted them why it was better to contact other dual licensees in their state to form their own Association for strategic reasons, and who else in their state had contacted the California Association. 1961ABA Ethics Committee issues Opinion 297 which for the first time declares that a dually qualified person “must choose between holding himself out as a lawyer or holding himself out as an accountant.” The Opinion purported to be a proper interpretation and application of former Canon 27, which prohibited unseemly advertising and self-laudation. ABA also issues informed Decision 565 which states separate letterheads will not satisfy Opinion 297 and condemns dual listings in directories. This got the attention of dual practitioners and dual licensees. First, they feared large CPA firms that were emerging from mergers, acquisitions and roll-ups of local firms all over the country. The tax attorneys worried that these CPA firms would eventually practice tax law in addition to accounting and would take work away from tax attorneys. Their fears were correct but they were unable to prevent that. The second turf war directed specifically at Attorney-CPAs was over two issues, (1) whether accounting practices were being used as “impermissible feeders” (solicitation) to law practices, and (2) whether Attorney-CPAs were holding themselves out as a “specialty” by informing the public that they were both. New York Association of Attorney-CPAs has its first meeting. 1962The Massachusetts Association of Attorney-CPAs has its first meeting. 1964Planning for AAACPA Members of the California, New York and Massachusetts Associations of Attorney-CPAs communicate about forming a National Association. Mailing lists of potential members in different states are compiled, the hotel is booked and advertisements are mailed to prospective members. During the week of October 12, 1964, also the last week of the World’s Fair in New York, members of the California, New York and Massachusetts Association meet in New York City at the Democratic Club to plan the first National meeting scheduled for that Friday evening through Sunday. 1964: After AAACPA was formedDavid W. Slavitt, CA On Oct 16-18, at the Concord Hotel in Kiamesha Lake, NY (P. Brent & H. Sidelle), the New York Association officers were installed and the American Association of Attorney-Certified Public Accountants, Inc. was formed. Care was taken so that we would be a national association and the members of one state chapter would not dominate our new organization. Louis Goldberg, who had published articles on dual rights, was the keynote speaker. (He had previously been asked by another group of dual licensees to join them and form a national association of attorneys and CPAs but they never did anything.) Sixty-five Attorney-CPAs from nine different states attended our first meeting. Twenty-three, or 35%, of those who attended declined to sign as charter members because they were unsure if this new Association would succeed in protecting their rights and they were concerned they would be reprimanded. Most of them ultimately joined AAA-CPA later. The California, New York, and Massachusetts Associations each became a separate state chapter of the American Association. 1965Louis Goldberg is voted to be an Honorary President. A decision is made to schedule smaller Spring AAA-CPA meetings in larger states which had no state Chapter and to recruit new members there. 1966An excellent article on dual practice, A Lawyer’s Paradox, is published in the Duke Law Journal, Winter 1966, pp. 117-141. It examined the arguments for and against the ABA Opinions and reviewed court decisions and constitutional questions that might be relevant in the event of contests in court and it supplied our Association with additional material to extinguish “brush fires” in several states, without judicial intervention. When a dual licensee who was a member or who contacted us was challenged, AAA-CPA would intervene, present briefs, and indicate that they were ready to litigate. The Bar Association backed down. In December, 1966, there appears, concurrently, in the ABA Journal and in the Journal of Accountancy, an article entitled “Accounting and Law: Is Dual Practice in the Public Interest?” That essay was authored by W.D. Sprague (CPA, New York) and Arthur J. Levy (Rhode Island Bar), the then co-chairmen of the National Conference of Lawyers and CPAs. The National Conference began a new attack on dual practice. Opinion 297 had been in force for well over five years, with no resulting restriction on dual practice. As the Bar Ethics Committee seemed to be accomplishing nothing, the National Conference, by these December 1966 articles (identical in the two Journals), sought to appeal to the membership at large, in both professions, “in the public interest” to put an end to dual practice. This new venture by the National Conference was a dismal failure. However, it provided our Association with a forum to present our views. To the credit of both Journals, they afforded us full publicity. An avalanche of “Letters from Readers,” all favorable to dual practice, descended upon both Journals; indeed, the Editor of the ABA Journal was moved to write this caption above one group of such letters: “Messars. Levy and Sprague Are Drawn and Quartered.” 1967In the March issue of both Journals appears a full-scale reply article to the National Conference article; one by Copal Mintz of the New York Bar and one by Philip D. Brent, CPA, New York. A committee of our Association meets with an AICPA group in New York. The principle theme for discussion was Independence. We were assured that dual practice continued to be no problem at the Institute. 1968The ABA Wright Committee, charged with re-working the ABA Code of Ethics, nears the end of its many hearings. The committee made a full-scale presentation, supplemented later by our furnishing each member of the Wright Committee complete documentation of the controversy (including all the material that our Association had produced to that time) . . . 26 Exhibits. 1969DR2-102 (E) (as adopted) of the Code of Professional Responsibilities of the American Bar Association reads: “A lawyer who is engaged in the practice of law and another profession or business shall not so indicate on his letterhead, office sign, or professional card, nor shall he identify himself as a lawyer in any publication in connection with his other profession or business.” 1970March: AAA-CPA produces an article discussing DR2 -102 (E) which is published in Wake Forest Law Review concluding that dual practice is proper if separate letterhead, sign and card is used. It stated, “This provision (DR2-102 (E)) seems so simple, so reasonable, so proper as to render difficult of belief the fact that it ‘definitely puts an end to the controversy that has raged in some quarters for more than 20 years’ (Wake Forest Intramural Law Review, March, 1970, page 191).” The article also stated, “There remains this problem: the extent to which and the manner in which, the public may be informed of – and the correlative right and duty of the lawyer to so acknowledge – the availability of the dual professional services . . . The precise question, then, becomes this: To what extent may a lawyer who is engaged in practice both as lawyer and as certified public accountant, identify himself publicly as a CPA? The only Disciplinary Rule, if any, that may seem to propose a prohibition of his identification as a CPA is DR2-102(E).” August: The National Conference publishes article in both the ABA and AICPA Journals asserting that the dual practitioner is “necessarily incompetent and a fraud on the public.” September: Louis Goldberg prepares a reply essay to the National Conference’s article, which ABA refuses to print and which is eventually published by AICPA in April of 1971. 1971August: ABA releases Opinion 328 which allows members to practice both professions from same office if in total compliance with all of the Code of Professional Conduct. Furthermore, Opinion 328 expressly concedes: “Accordingly, this Committee cannot condemn any activity today on the basis of ‘indirect solicitation’ or ‘feeding’ of a law practice. Any proscription must be based upon the provisions of the code.” We won this and other battles because we pooled our monetary and manpower resources in a national organization and we were aggressive, intelligent, tenacious, and persistent in defense of our position which was legally correct. 1976The National Conference revised its 1970 study and deleted its derogatory references to dual practice (victory long delayed), but it states that an attorney providing legal services may not also issue an audit opinion for the same client, if he or she is not considered to be “independent.” 1977June: U.S. Supreme Court in Bates case liberalizes rules on publicity causing states to revise attorney advertising rules. 1994Why Dual Rights remains important: “Those who cannot learn from history are doomed to repeat it.” April: Eighteen years after the National Conference deleted its derogatory references to dual practice, twenty-one years after ABA Opinion 328, which allowed members to practice both professions from the same office, twenty-two years after DR 2-102 (E) becomes effective, and seventeen years after the Bates decision, the Supreme Court issues the Ibanez decision. The Court was unanimous on her commercial free speech right to inform the public that she is dually licensed. For the first 12 years after AAA-CPA was formed and for 18 years prior to that, the AICPA was a valuable ally of ours. 2014AAA-CPA celebrates 50th Anniversary. 2015Name changed to American Academy of Attorney-CPAs. |